As media that grant their consumer agency, games are forced to tackle choice and consequence more directly than most. I guess one facet of this is the debate over whether or not legitimising certain actions in-game can translate to real-world acts of violence, but I’d rather take this conceptual train to the next stop and look more specifically at how games implement morality mechanically. So I’ll do that.

Morality is a difficult thing to capture when you (obviously) can’t account for the actions of the protagonist. In film or TV, creators know 100% that the protagonist is going to kill his wife, because that’s what they wrote, and they’re free to paint a moral picture around it. In a game, assuming a certain level of choice of course, the protagonist might not kill their wife. They might give her some freshly picked herbs. They might not get married in the first place.

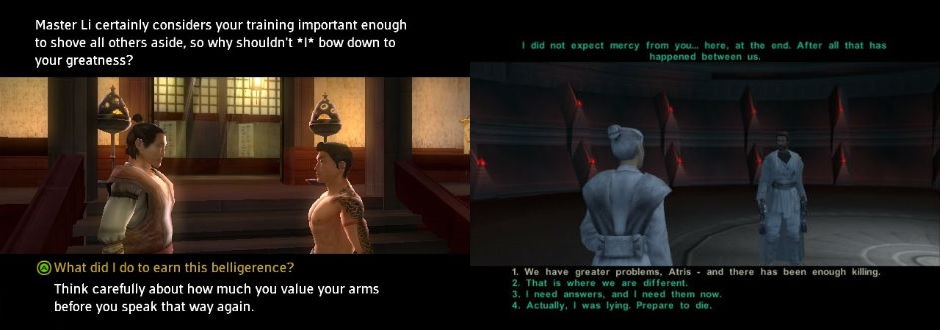

Probably the most basic examples of morality mechanics come from (mainly Bioware) RPGs like Knights of the Old Republic and Jade Empire. These place morality as strict binary, i.e. in any given situation you can either be so lovely that you induce vomiting in everyone with an IQ above 50 or so directionlessly evil that your smiles cause calf cramps. And, if you reasonably decide that some middle ground might be good, you’re wrong. You’re the hero. Heroes don’t do grey. Grey is for accountants, Jamie Dornan and the weak.

So you, as the hero, arrive in a new city on your quest to save your prince or duchess or stepson during a war or thunderstorm or crippling cholera epidemic, and a poor, hungry child asks you for some cake. The law of moral binaries dictates you have one of two responses:

1: ‘Sorry child. I dispense justice, not cake, and would never harm the arteries of a minor. Take this sprig of parsley.’

2: ‘No. Give me your shoes.’

The effect either one has on your morality is captured on a sliding scale in the character screen: being good moves you up; being bad, down. It’s an odd idea, because it turns morality into a kind of net resource, implying that sucker-punching a four-year-old is fine as long as you counterbalance it with community outreach.

Now, although black and white morality systems like this are essentially trying to capture potentially the most complex of human characteristics on a thermostat, you can’t condemn them entirely. It’s easy enough to see where they come from. You just have to look at the RPGs that make use of them, namely the aforementioned KOTOR and Jade Empire. One is rooted in Star Wars and the other in Chinese wuxia. Morality in those kinds of stories does tend to be relatively black and white, because they’re often about evil emperors and idealistic rebels and love and all that.

That’s why Yoda says things like ‘luminous beings we are’ that make you think he’d stick a daisy in a rifle if he was three feet taller. That’s why the emperor says things like ‘Let the hate flow through you’, things so evil that if you actually rationalise them you realise that they definitely shouldn’t be coming from the lips of what is essentially a political figure - political evil should be subtle, and this is the equivalent of seeing Boris Johnson attempting to summon an Elder God.

So, when your options in KOTOR are ‘Shiv’ or ‘Kiss’ when someone asks you where the toilet is, it’s not as much of a departure from the films’ morality as you might think, but it just doesn’t quite fly in a game…

Morality of this type works in film precisely because the viewer has no agency. Either they identify with the hero and get a vicarious rush watching an ordinary person do extraordinarily lovely things to take down someone extraordinary doing awful things, or the hero is so good as to be beyond identifying with, and the enjoyment simply comes from watching what they’re capable of achieving in the face of pure evil. The fact that these either aren’t the choices we’d make or are choices we couldn’t make if we tried is part of what makes it work. There’s a level of childlike aspiration to it.

Games are different. Just because a game gives us the ability to do utterly heroic or utterly evil things doesn’t mean it will succeed in giving us the inclination. Now it’s us making the choice, and we’re not film characters, so the fact that we wouldn’t pick either of these yin and yang options is now actually a problem. Plus another key thing in (good) film is that however sickly sweet the hero’s choices and however encrusted in mould the villain’s, we’re never made aware of an underlying mechanism.

Morals are like those vacuum-packed bacon cubes you sometimes see under all the normal meat in the corner shop: you may want them in your stew but definitely don’t want to know which parts of the vole they were carved from. The slider mechanism ends up feeling cheap because it shows you what your choices really are: transactions. Being good or bad is just another way of collecting something, rather than a tough moral dilemma in and of itself.

On the tier just above this are the very slightly more complicated morality systems in games like Red Dead Redemption and the Mass Effect and Fallout series, each of which take aslightly different slant on binary morality.

While the former keeps the ‘morality as resource’ angle (in this case ‘honor’), actions that increase or decrease its value benefit from a lack of bright neon signposting. It doesn’t boil down to a binary dialogue choice, rather killing a nun offhand or giving out bribes will decrease it while bringing in bounties or assisting the law will increase it. It’s also linked to your ‘fame’ level, meaning NPCs will react to your morality if you’re well-known enough. Basically, the mechanism is equally binary but a little more seamlessly integrated into the game.

Fallout has a similar system in ‘Karma’, though from Fallout 3 onwards the numeric value is hidden from the player, presumably to help keep the game immersive.

Mass Effect separates the good from the bad to eliminate the ‘cancelling out’ issue of a single morality value, meaning whatever you do, you can’t erase that horrific murder you committed four hours in, no matter how many bouquets you give the widow.

All of these, however, suffer from the same problem: noticeable mechanisms. Jade Empire, KOTOR, Fallout and Mass Effect all give you stuff for being at certain levels of morality. All four give you unique dialogue options based on your morality, while the former two literally give you access to new powers if you’re good or bad enough.

This is fine in principle. Games give you stuff for achieving stuff. That’s how they work. This just isn’t the area in which to implement it. It affects the nature of any moral choice, because you’re driven to at least partly base your decision on that mechanism, which may well not be the call you, or your created character, would make.

You might, for example, kill someone in Jade Empire because you want to follow the sort of evil ‘Way of the Closed Fist’ so you can learn a spell that lets you throw a bunch of rocks at people. You’ve not made that choice based on the situation as written. You’ve been given a ‘meta’ incentive, a points system outside the world of the game that’s influencing your decision within. Equally, shifts in your dialogue options as a result of one or two actions that you only took to get sweet stuff can make you feel like your character is changing without you. These are the opposite of immersion.

I reckon the overarching flaw here is a focus on consequence over choice. There will definitely be people who will disagree here, and obviously consequence is a huge part of what makes a choice meaningful, but what these choices really lack is the ability to speculate. If you kill an innocent in Red Dead, you know you’ll lose honor. If you’re a sarcastic arse in Mass Effect, you know you’ll gain Renegade (naughty) points. If you save a prisoner from his pod rather than gassing him in KOTOR, you know you’ll move towards the light. You know what you have to do to get good points; you know what to do to get bad points. Once you’ve decided what you’re going for, choices suddenly have immediate, tangible, beneficial consequences that go against the very idea of realistic in-game morality by separating the choice from the story.

Dragon Age: Origins avoids this quite well, firstly by having no overt morality system at all and secondly by having the main consequences of any moral choices be the varied reactions of your companions. Although there are still many obviously good and obviously evil choices, it’s interesting when a seemingly middle of the road choice offends your more noble friend or when what you thought was virtuous gets you a high five from an amoral witch.

But for the best morality mechanics we sadly have to change the locks on our terraced house and leave RPGs standing in the rain with a box of their things. RPGs run on binary morality because they are so often grand sweeping narratives about good vs evil; darkness coming back into the world; lightness hailing a taxi; neutrality not existing apart from a few guys in a forest maybe.

Good and evil tend to be drawn in sharpie. There are more interesting moral questions to explore, ones that really aren’t that difficult to implement mechanically. Probably the best, in game terms, is practicality vs ethics.

Take Paper’s Please, a game in which you are placed in the role of immigration inspector for a fictional country. You’re forced to weigh up the financial wellbeing of your character, and their family, against the people (some of them desperate) who want to enter your country. If someone just wants to enter the country to join their partner, but their papers are slightly off, do you let them in and risk your own position or coldly turn them away in case they pose a risk themselves? The choice is made difficult by the fact that you have no idea what’s right, and no idea whether ‘right’ will even benefit you.

But my favourite, by virtue of a mechanic that seems like it should undo itself, is Life is Strange, a narrative game structured around moral choices, in which you have the ability to rewind time a minute or two. You’d think being able to go back in time would devalue any moral choice. Make a choice that results in the unintended removal of your trousers? Nip back a few minutes and ensure those stalks stay covered. The game avoids this by making sure every choice has mixed results.

You see the security guard for Blackwell Academy (the game’s setting) shouting at a distressed student. You step in and the security guards anger turns to you. He’s probably not someone you want to be on the wrong side of, so you rewind and leave it. Now the student stares as you let it happen. Future encounters with her aren’t going to be easy. You’ve seen another student at the school brandishing a gun, but you can’t prove it and his father holds a lot of sway here. Tell the principal, risk not being relieved and potentially gain a reputation for lying? Or leave it, try and find some evidence, but now any awful thing that happens is on your head for keeping quiet?

That’s the interesting thing. You are given a set of immediate consequences, ones you could reasonably predict, but are left to wonder at their consequences. Life is Strange, like many games of its type, has been criticised for offering the illusion of meaningful choice without actually paying off in consequence, and I totally understand that point. What it does, however, is nail the actual choice itself.

This is what a lot of games lack, a convincing division of positive and negative as a potential, predictable result of every choice, rather than as the choice itself. It’s rare in life to come across a choice (a big one, not which type of pepperami you want), for which there is an entirely positive option.

Life is Strange manages to simulate dilemma by allowing you to speculate in real time, to actually see the initial consequences but not the long term ones. It’s a good approximation of actual decision making. You work with initial, predictable consequences (if I’m honest about my friend’s leopard-print trilby, they’ll get offended but it might save them later embarrassment, or I could tell them it’s nice and stay on their good side, but they might find out later and feel worse), and are forced to re-evaluate retrospectively as the unpredictable after-effects come into play (oh, it was a gift from their dying uncle/ oh, they were trying to look stupid and now I look a div for genuinely saying it looked fly).

These choices aren’t complex (sometimes still to a fault), they just implement morality with a mix of four components (the predictable, the unpredictable, the practical, the ethical) as opposed to two (this is good, this is not). That’s all it takes. Two extra variables and a lack of overt meta-systems (bars, rewards, powers) guiding your choices.

Even with the more rudimentary good/evil morality systems, your choices can have real sway. Characters may come and go; people may die; strangers may judge you. The consequences of your actions often feel like part of the story.

But so should the choices.

Share